NEWS NOT FOUND

Dissatisfaction with life in UK unchanged since Covid, official data shows

The proportion of people in the UK who feel dissatisfied with life has failed to improve since the pandemic despite the economic outlook improving, official figures show.The Office for National Statistics said a survey of personal wellbeing in the UK showed average life satisfaction remained below its pre-pandemic peak, despite the rate of gross domestic product per person rising since 2021.The report also flagged the more recent decline in living standards, pointing out that UK GDP per person fell in the third and fourth quarters of 2025.The ONS also said trust in the UK government remained low, with about one in five adults (21.9%) in Great Britain reporting trust in December 2025 to January 2026

Netflix quits Warner Bros takeover battle; FTSE 100 ends week at record high – as it happened

The market reaction to Netflix walking away from Warner Brothers indicates all sides have done well, suggests Matt Britzman, senior equity analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown.With Netflix and Paramount’s shares both up almost 9% in pre-market trading, Britzman says:double quotation markThe streaming takeover saga took a dramatic turn after Warner Bros. Discovery formally recognised Paramount Skydance’s offer as the superior bid, prompting Netflix to walk away almost immediately. After weeks of drama, meetings and speculation, Netflix’s decision to step aside brought an abrupt end to what had been one of the market’s most closely watched corporate chess matches. In the end, it underlined just how fast things can move when big money, regulators and strategic pride collide

BA owner’s profits rise by 20% despite drop in passenger numbers last year

British Airways’ owner, International Airlines Group, has announced a sharp rise in annual profits to almost £4bn despite a slight fall in passenger numbers in 2025.Pre-tax profits across IAG increased by 20% to €4.5bn (£3.9bn), with record operating profits on margins of more than 15% at BA and its sister airline Iberia.The group’s chief executive, Luis Gallego, said the lucrative transatlantic market, also served by IAG’s Aer Lingus and Level airlines, remained robust, after warnings of softening demand in the autumn

Sainsbury’s to cut 300 jobs as it restructures tech team and Argos deliveries

Sainsbury’s is cutting 300 head office jobs as it restructures its technology team and Argos delivery network, creating more separation between the two businesses.The London-based retail group said most of the job cuts would be in technology and data, where it was “consolidating routine reporting tasks” and creating dedicated teams for Argos and the supermarket.The changes also include restructuring the local delivery hubs for Argos, where teams’ shifts will change so they are working more regular hours with less overtime.Regional store directors for the Sainsbury’s Local convenience store chain are also being introduced to help drive that part of the business.The latest changes come after Sainsbury’s decided to invest more in technology to improve efficiency at its business, including AI forecasting tools and warehouse robotics

Trump says affordability crisis is over. Voters and data disagree

The affordability crisis is over, Donald Trump told the US on Tuesday. The president’s state of the union address put the blame for soaring prices squarely on the “dirty, rotten” lies of the Democrats and claimed prices were now “plummeting downward”.“Soon you will see numbers that few people would think were possible to achieve just a short time ago,” Trump said.But more than a year since he was sworn in to office, stubborn inflation and Trump’s chaotic trade policies, have done little to assuage consumers’ fears about the cost of living. Poll after poll shows that, as far as voters are concerned, “affordability” is still very much an issue

Hornby sells slot car racing brand Scalextric for £20m

For almost six decades Hornby has watched Scalextric drive revenues for its hobby business but on Friday the company said it had decided to sell the slot car racing brand for £20m to a little-known buyer.The model railway company, which also sells toy planes and cars under the Airfix and Corgi brands, has sold the Scalextric business and intellectual property rights to Purbeck Capital Partners.Kent-based Hornby, which experienced a hobby boom during the Covid pandemic, has owned Scalextric since 1968. Invented by Fred Francis, the very first Scalextric set was made in Hampshire in 1956.On Friday, Hornby’s parent company, Castelnau, which also owns businesses including the funerals firm Dignity, said it was selling the toy car racing business to Purbeck Capital Partners

Jack Dorsey to cut 4,000 jobs due to AI advances at Square parent Block

Woman at heart of US trial says she was addicted to social media at age six

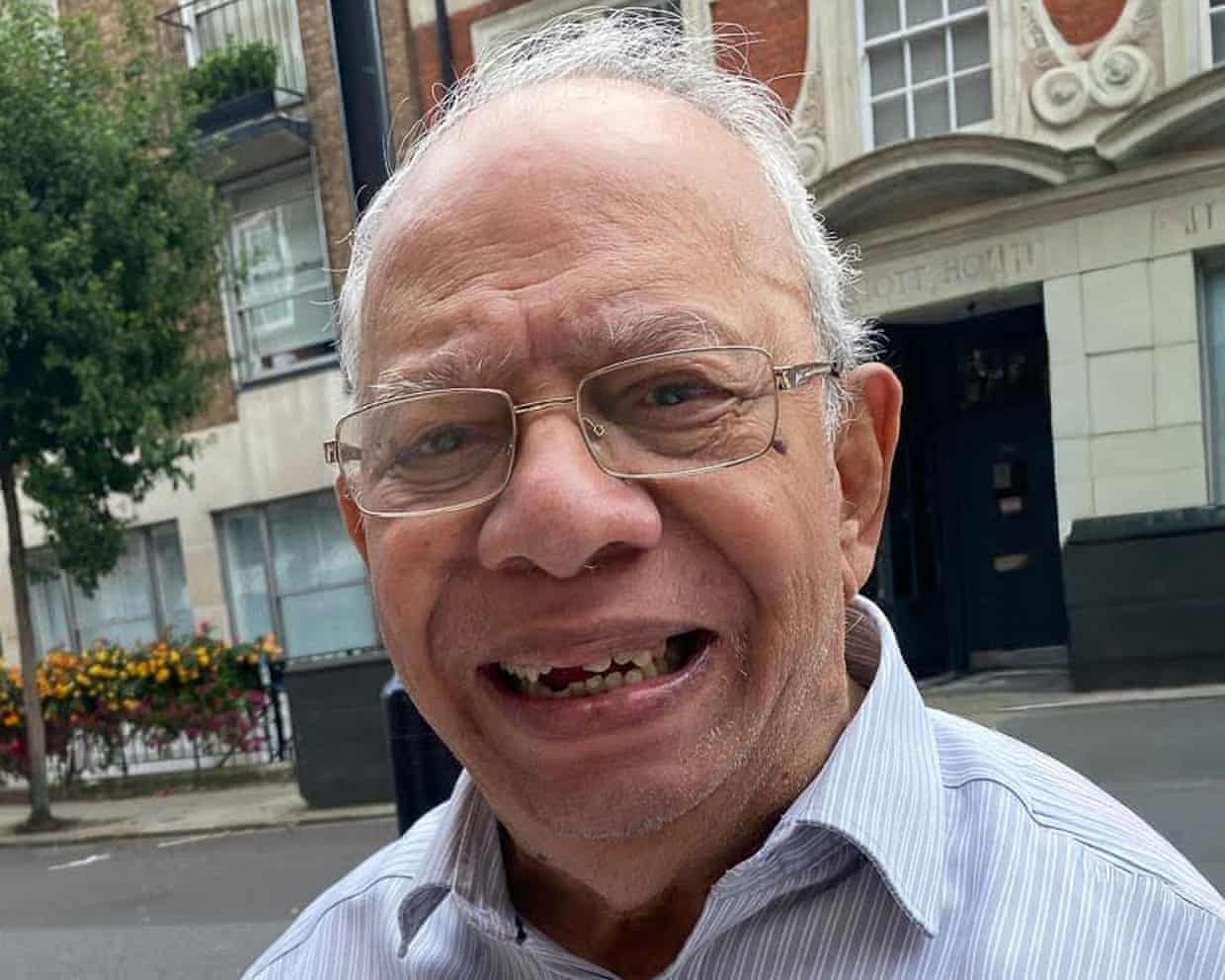

Riaz Hasan obituary

Met police to pilot facial recognition identity checks, mayor confirms

Tell us: how will the UK’s landline switch-off affect you or your family?

‘Unbelievably dangerous’: experts sound alarm after ChatGPT Health fails to recognise medical emergencies