NEWS NOT FOUND

Naples museum to allow visually impaired visitors to experience art through touch

The Sansevero Chapel Museum in Naples will allow dozens of visually impaired visitors to take part in a rare tactile experience, letting them touch celebrated works of art including the Veiled Christ, which is widely regarded as one of the most striking masterpieces in the history of sculpture.On 17 March, the museum will host an initiative called La meraviglia a portata di mano – Wonder within reach – organised in partnership with the Italian Union of the Blind and Visually Impaired of Naples, offering about 80 blind and partially sighted visitors a chance to encounter the marble masterpieces.Visitors will be guided through the chapel by guides who are also visually impaired in a programme designed to place accessibility at the centre of the museum experience.The protective barrier surrounding the sculptures will be removed, allowing participants, wearing latex gloves, to explore by touch the intricate marble surface of the sculptures including Giuseppe Sanmartino’s Veiled Christ, which depicts Jesus covered by a transparent shroud made from the same block as the statue. The tactile route will also extend to the reliefs at the feet of the sculptures La Pudicizia and Il Disinganno

Jimmy Kimmel on Pentagon splurging on doughnuts: ‘Is this My 600lb Defense Department?’

On late-night shows, hosts poked fun at the Trump administration’s inconsistent messaging on the Iran war, Pete Hegseth splurging on high-end food at the Pentagon and New York’s John F Kennedy Jr lookalike contest.On what Jimmy Kimmel called “day 11 of Jabba the Hutt’s war on Iran”, the host focused on Trump’s mixed messages over the Middle East conflict.“Trump said yesterday that the war could end very soon, which would be encouraging, had be not also told us he’d end the war in Ukraine in 24 hours,” said Kimmel.“He’s going to make a huge mess and walk away like it’s the new toilet in the Lincoln bathroom.”Kimmel then turned to reports that Pete Hegseth, the US defense secretary, spent $93bn of US taxpayer money last year, including millions of dollars in September on luxury food items: “$2m on Alaskan king crab, $6

Rapper Lil’ Kim to headline both Vivid Sydney and Melbourne’s 2026 Rising festival

The pioneering female rapper Lil’ Kim will headline both Vivid Sydney and Melbourne’s Rising this year, as each festival revealed its programs on Wednesday.The performances at Sydney’s Carriageworks and Melbourne’s Festival Hall will be Lil’ Kim’s first Australian shows in 15 years, celebrating her landmark multiplatinum records Hard Core – which turns 30 this year – and The Notorious KIM.Both Vivid and Rising are staged annually in winter.Rising’s artistic director and chief executive, Hannah Fox, said the 51-year-old rapper, who broke out as a member of Junior MAFIA and was mentored by the Notorious BIG, was on “a really exciting return to form”.“Hard Core and Notorious KIM really did carve a path – there are so many women rappers and femcees now who absolutely followed in her tiny footsteps, her funked-up, sex-positive vibe,” Fox said

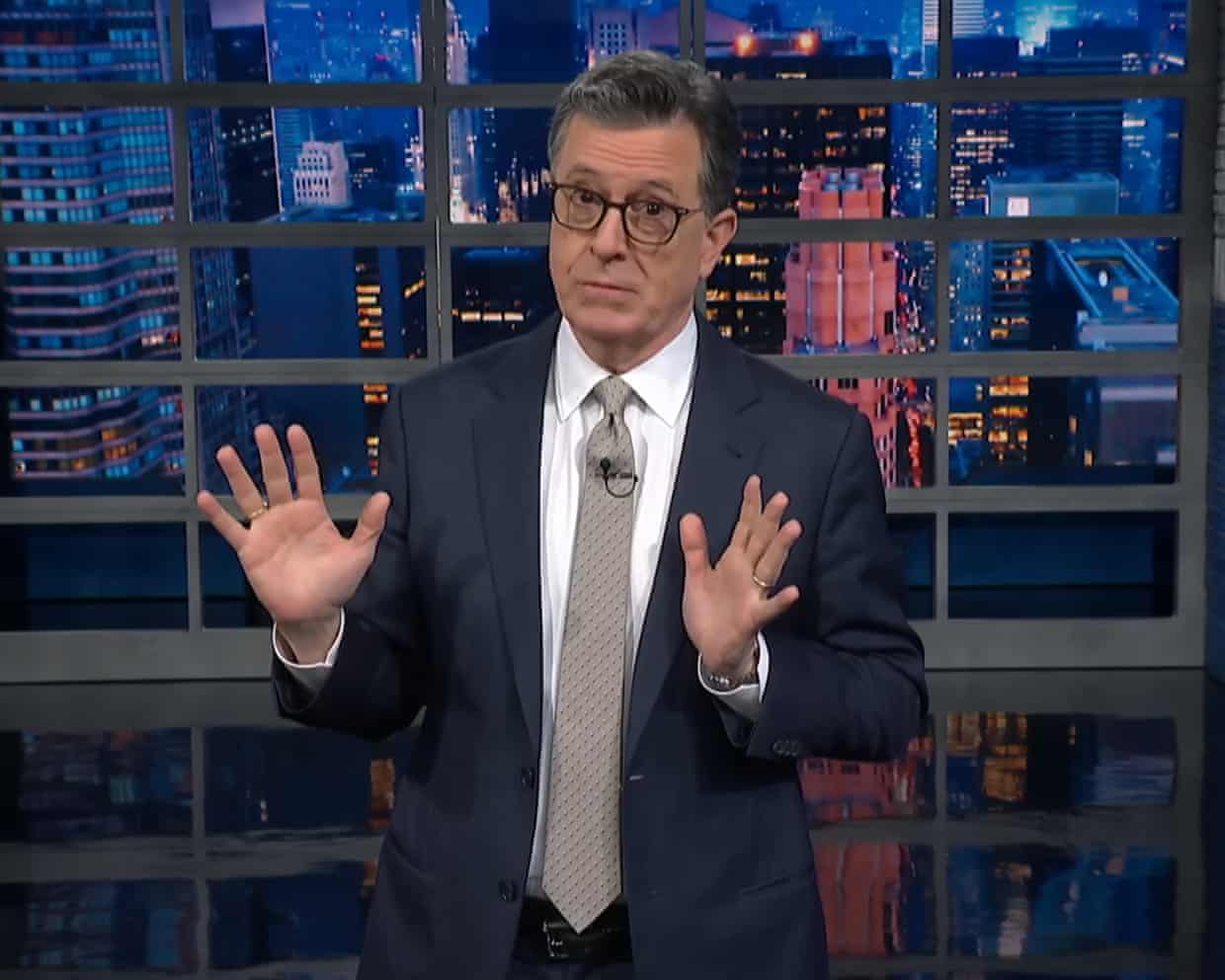

Stephen Colbert on US war in Iran: ‘We’re still no closer to learning what the goal is’

Late-night hosts looked into the murky goals, economic impact and disrespect for military protocol of Donald Trump’s war in Iran.“We’re on day 10 of the Iran war,” said Stephen Colbert on Monday evening, “and we’re still no closer to learning what the goal is. Is it regime change? Is it ending a nuclear program? Is it changing the name to Donald Trump’s Iran-a-Lago?”“But we are learning more about the cost,” he noted, as the first week of the war alone is estimated to have cost about $6bn. “Do you know what you could buy with $6bn? Twenty-seven Kristi Noem horsey commercials!” he joked before clips of the very expensive, controversial ad campaign that likely ended Noem’s tenure as secretary of homeland security.Despite the exorbitant cost, Trump said over the weekend that this new surprise war would stop only after Iran’s “unconditional surrender”, to which Iran replied: “That’s a dream that they should take to their grave

Leap Year is patently ridiculous and widely panned. It’s also the perfect romcom

In 2010 the Guardian gave the romcom Leap Year a one-star review. The script was “horrendous”, according to the reviewer: “Afterwards, the only ‘leap’ I felt like making was off a motorway gantry into the fast lane of the M25.”He wasn’t alone. Leap Year has an approval rating of 23% on Rotten Tomatoes; the New York Times called it “so witless, charmless and unimaginative that it can be described as a movie only in the strictly technical sense”.It has been 16 years

Womadelaide 2026 review: Grace Jones embraces the compulsion for dancing in the dark times

Botanic Park, AdelaideNo matter the music, no matter the mood, the festival crowd moved and moved – in a celebration embodied by the liberated, messy and sexual stylings of the 77-year-old headlinerGet our weekend culture and lifestyle emailStraight away, the atmosphere at Womadelaide is calmer this year. On opening night, it is only 25C – the warmest it is forecast to be all weekend. After two years of temperatures in the 40s, this will be a festival to ease into. Even the bat colony at the entrance feels decidedly more settled. “I hear we missed a really hot one last year,” says Beoga’s Niamh Dunne later that night

Bleak economic data shows UK plc in trouble well before Middle East crisis

UK economy unexpectedly flatlined in January, official figures show

Keeping it simple was always the answer for John Lewis | Nils Pratley

Watchdog puts UK fuel retailers ‘on notice’ over profiteering from Iran war

Middle East war creating ‘largest supply disruption in the history of oil markets’

Antibiotics need coordinated G7 investment | Letter